Navigating the world of version control can sometimes feel like walking a tightrope. Mistakes happen, code gets broken, and sometimes, you need a way to rewind the clock. This guide focuses on how to use `git revert` to undo commits safely, providing you with the knowledge and techniques to gracefully recover from errors and maintain a clean project history.

We’ll explore the core concepts of `git revert`, differentiating it from other Git commands like `git reset`. You’ll learn how to identify the commits you need to undo, the importance of backing up your work, and how to handle potential merge conflicts. From basic syntax to advanced techniques, this guide will equip you with the skills to confidently revert commits and keep your projects on track.

Understanding Git Revert

Git’s version control system provides powerful tools for managing code changes. Among these, `git revert` stands out as a safe and reliable method for undoing specific commits. This approach ensures that the history of your project remains intact while allowing you to correct mistakes or remove unwanted changes.

Purpose of `git revert`

The primary function of `git revert` is to create a new commit thatundoes* the changes introduced by a specific commit. It does not alter the existing commit history. Instead, it generates a new commit that effectively reverses the effects of the targeted commit. This makes `git revert` a non-destructive operation, preserving the integrity of your project’s timeline. This is particularly useful when you need to remove a problematic change without losing the history of the commit itself.

Comparison: `git revert` vs. `git reset`

Both `git revert` and `git reset` can be used to undo changes, but they operate very differently. Understanding their distinctions is crucial for choosing the appropriate tool for the task.

- `git revert`: Creates a new commit that

-undoes* the changes of a previous commit. The original commit remains in the history. This is a safe and non-destructive operation. It’s ideal for undoing changes that have already been shared with others or pushed to a remote repository. - `git reset`: Alters the commit history by moving the branch pointer to a different commit. It can discard commits entirely or keep them as uncommitted changes. `git reset` is a destructive operation, as it modifies the commit history. It’s generally used for local, unshared changes.

The key difference lies in how they handle the commit history. `git revert` preserves the history, while `git reset` rewrites it.

The “Revert Commit”

When you use `git revert`, Git creates a new commit known as the “revert commit.” This commit contains theinverse* of the changes introduced by the commit you’re reverting. The revert commit effectively cancels out the changes made by the original commit.

The revert commit’s message typically includes a reference to the original commit being reverted, making it easy to track the history of changes and understand why a specific commit was undone.

This new commit is then added to your branch, creating a clear record of the change and its reversal. This process maintains a complete audit trail of your project’s evolution. The original commit remains in the history, providing context and allowing you to easily track the progression of your code.

Safe Reverting

Reverting commits in Git is a powerful tool, but it’s crucial to approach it with caution. Improper use can lead to data loss or conflicts, especially in collaborative environments. Before you begin the process of reverting, it’s important to understand the potential pitfalls and take preventative measures.

Backing Up Your Repository

Before making any significant changes to your Git history, including reverting commits, it’s highly recommended to back up your repository. This ensures that you have a safety net in case something goes wrong, such as accidentally reverting the wrong commit or encountering unexpected merge conflicts.

- Creating a Backup: The easiest way to back up your repository is to create a bare clone. This is a complete copy of the repository, including its history and branches. You can do this using the following command:

- Alternative Backup Methods: Another method is to simply copy the entire repository folder to a safe location. However, this approach might be less efficient for large repositories. You can also use cloud-based backup services or version control systems to back up your repository.

- Importance of Regular Backups: Regular backups are crucial for disaster recovery. If you experience data loss due to a failed revert or any other issue, you can restore your repository from the backup. Consider automating the backup process to ensure that it’s done consistently.

git clone –bare /path/to/your/repository /path/to/your/backup.git

Potential Risks of Reverting Commits

Reverting commits, especially in shared repositories, can introduce several risks that need to be carefully considered. Understanding these risks helps you mitigate potential issues and maintain a stable codebase.

- Loss of Work: Reverting a commit effectively removes the changes introduced by that commit. If the commit contains important code changes, you’ll lose that work unless you can recover it from a backup or other source.

- Merge Conflicts: If the commit you’re reverting has already been merged into other branches, reverting it can lead to merge conflicts when those branches are merged back into the main branch. Resolving these conflicts can be time-consuming and complex.

- Team Collaboration Issues: In a shared repository, reverting a commit can disrupt the work of other developers. If another developer has based their work on the commit you’re reverting, their changes might become outdated or require significant rework.

- History Rewriting: Reverting a commit alters the Git history. While this is often the desired outcome, it can create confusion if not communicated effectively to the team. It’s important to inform other developers about the revert and the reasons behind it.

- Unexpected Side Effects: Reverting a commit can sometimes have unintended side effects. For example, if the commit introduced a database schema change, reverting it might lead to data inconsistencies or application errors.

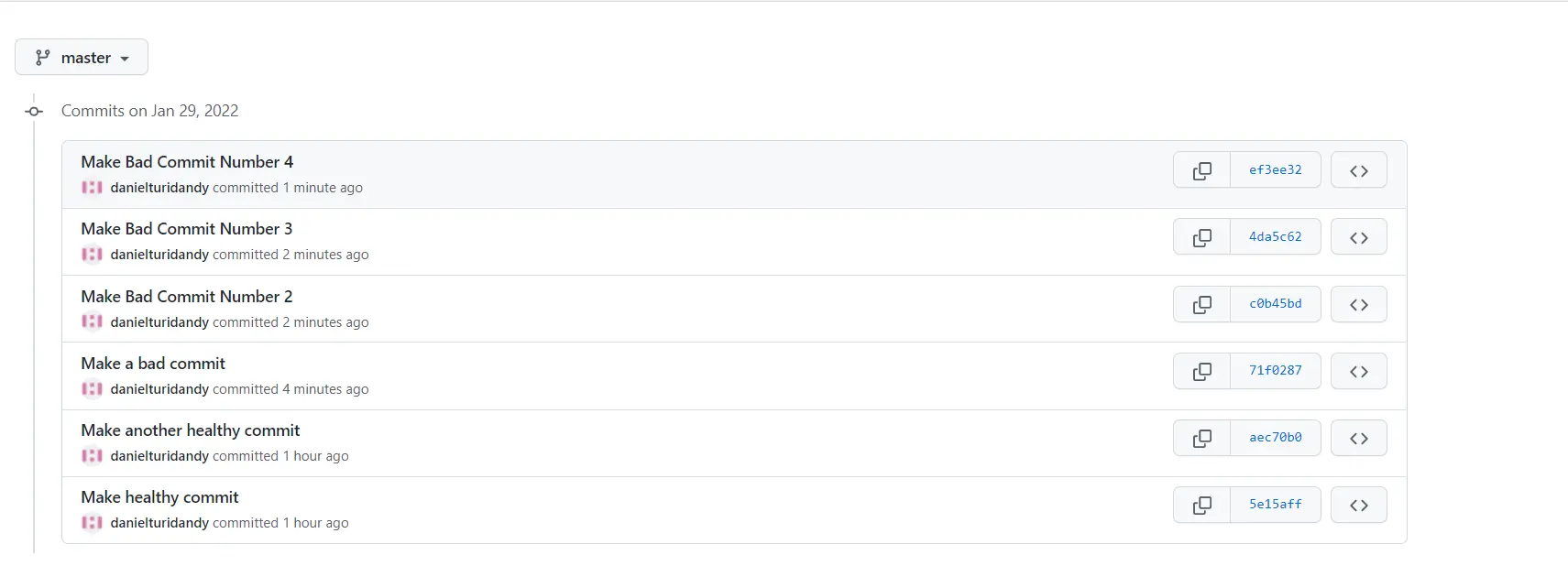

Checking the Commit History

Before reverting any commit, you need to identify the specific commit you want to revert. This involves examining the commit history to understand the changes introduced by each commit and to locate the commit you wish to undo.

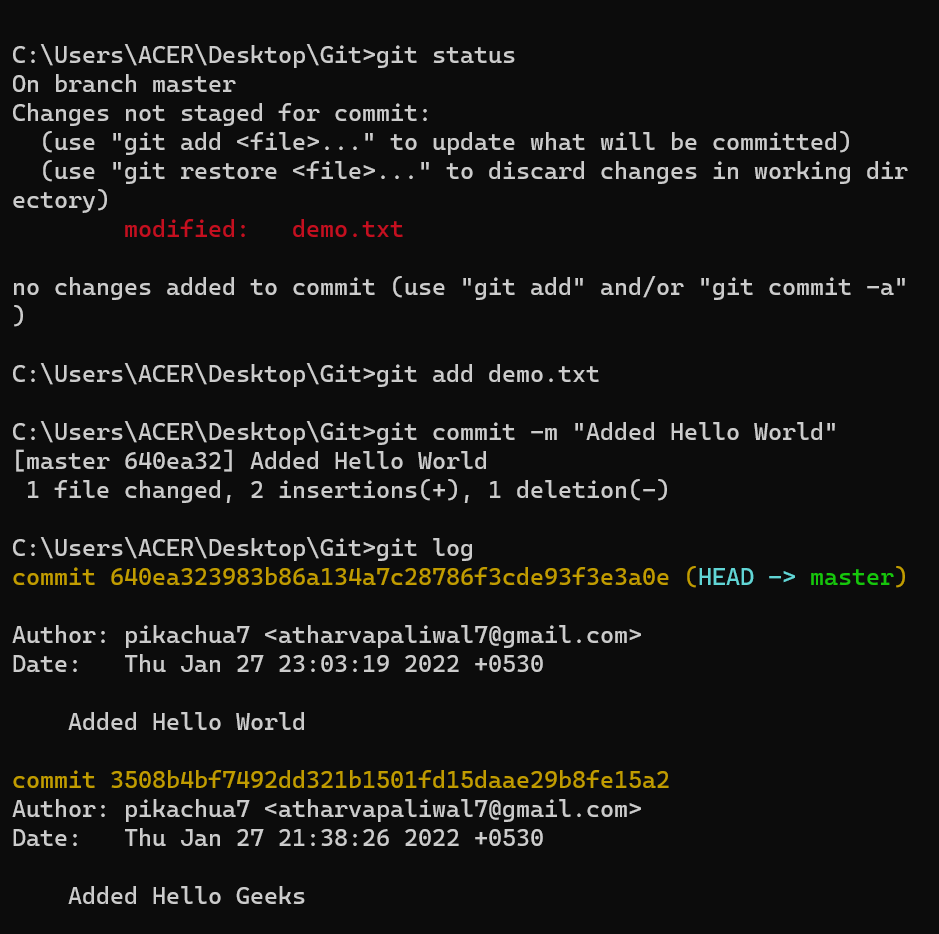

- Using `git log`: The `git log` command is the primary tool for viewing the commit history. It displays a list of commits, including their commit hashes, author, date, and commit messages. You can use various options with `git log` to customize the output.

- Identifying the Commit to Revert: Carefully examine the commit messages and the changes introduced by each commit to identify the one you want to revert. Pay attention to the date, author, and the description of the changes. The commit message should clearly indicate the purpose of the commit.

- Understanding Commit Hashes: Each commit has a unique identifier called a commit hash, which is a long string of characters. You’ll need the commit hash to revert the commit. You can copy the commit hash from the output of `git log`.

- Using Graphical Tools: Git also offers graphical tools, such as GitKraken, SourceTree, or the Git integration in your IDE, to visualize the commit history. These tools can make it easier to navigate the history and identify the commit you want to revert. They often provide a visual representation of branches and merges, making it easier to understand the relationships between commits.

git log –oneline

This command displays the commit history in a concise format, showing only the commit hash and the commit message on a single line.

git log -p <commit-hash>

This command displays the changes introduced by a specific commit. Replace <commit-hash> with the actual commit hash. This is particularly helpful for verifying the content of the commit before reverting it.

Executing the Git Revert

Now that you understand the concept of Git revert and the importance of safe reverting, let’s dive into the practical steps of executing the `git revert` command. This involves understanding the basic syntax and how to handle potential complications, such as merge commits and merge conflicts.

Basic Syntax of Git Revert

The core command for reverting a commit is `git revert`. It takes the commit hash of the commit you wish to undo as its primary argument.To revert a specific commit, you would use the following syntax:

git revert <commit_hash>

Replace `<commit_hash>` with the actual SHA-1 hash of the commit you want to revert. You can find the commit hash using commands like `git log`. When you run this command, Git will:

- Create a new commit that undoes the changes introduced by the specified commit.

- Open a text editor, allowing you to modify the commit message for the revert commit. By default, Git provides a message that includes the original commit message and indicates that it’s a revert.

- Apply the changes to your working directory and stage the changes for the new revert commit.

For instance, if you wanted to revert a commit with the hash `a1b2c3d4`, you would execute:

git revert a1b2c3d4

Git will then create a new commit that reverses the changes introduced by `a1b2c3d4`. This new commit will have a different hash and will be applied on top of your current branch.

Reverting Merge Commits with the `-m` (Mainline) Option

Reverting merge commits requires special consideration because a merge commit combines changes from multiple branches. Git’s `-m` option specifies which parent branch should be considered the “mainline” when reverting the merge. A merge commit usually has two parents (or more for octopus merges): the branch being merged into, and the branch being merged from. The `-m` option tells Git which parent to use as the base for the revert.The `-m` option takes an integer argument, which represents the parent index.

The parent index starts at 1.

- `git revert -m 1 <merge_commit_hash>`: This option considers the first parent as the mainline. This effectively reverts the changes introduced by the branch that was merged

-into* the current branch. - `git revert -m 2 <merge_commit_hash>`: This option considers the second parent as the mainline. This reverts the changes from the branch that was merged

-from* the current branch.

To determine which parent is the “mainline,” you need to understand the merge history. Typically, the first parent (index 1) is the branch you were on when you performed the merge, and the second parent (index 2) is the branch that was merged in. Use `git log -p –merge <merge_commit_hash>` to examine the merge and understand the changes and parent relationships.For example, if you have a merge commit with the hash `f4e5d6c7`, and you want to revert the changes from the branch that was merged into your current branch, you would use:

git revert -m 1 f4e5d6c7

Conversely, to revert the changes from the branch that was merged

from*, you would use

git revert -m 2 f4e5d6c7

Choosing the correct mainline is crucial; selecting the wrong parent can lead to unexpected results and potentially introduce further complications.

Handling Merge Conflicts During Revert

Merge conflicts can occur during the `git revert` process, particularly if the commit you are reverting introduced changes that conflict with current changes in your branch. Git will stop the revert process and mark the conflicting files. You must then resolve the conflicts before completing the revert.The process for resolving merge conflicts during a revert is similar to resolving merge conflicts during a regular merge.

- Identify Conflicting Files: Git will indicate which files have conflicts. These files will contain conflict markers (e.g., `<<<<<< HEAD`, `=======`, `>>>>>> <branch_name>`).

- Edit the Conflicting Files: Open the conflicting files in a text editor and manually resolve the conflicts. This involves choosing which changes to keep, combining changes, or rewriting the code to resolve the conflict. Remove the conflict markers.

- Stage the Resolved Files: After resolving the conflicts in each file, use `git add <file_name>` to stage the changes.

- Continue the Revert: Once all conflicts are resolved and the files are staged, run `git revert –continue`. This will complete the revert process and create the revert commit. If you change your mind, you can use `git revert –abort` to cancel the revert and return to the state before you started.

For example, let’s say you’re reverting a commit and encounter a conflict in `my_file.txt`. After editing `my_file.txt` to resolve the conflicts and removing the conflict markers, you would execute the following commands:

git add my_file.txt

git revert --continue

This process ensures that Git creates a new commit that correctly reverts the original changes while incorporating the necessary adjustments to handle any conflicts.

Handling Merge Conflicts During Revert

When reverting commits, especially those involving significant changes or affecting the same lines of code as subsequent commits, merge conflicts can arise. These conflicts require careful resolution to ensure the integrity of the codebase. The process involves identifying the conflicting changes, choosing the correct versions, and merging them to create a clean, reverted state.

Steps for Resolving Merge Conflicts During `git revert`

Resolving merge conflicts during `git revert` involves a structured approach to reconcile conflicting changes. The following steps Artikel the process:

- Identify the Conflict: Git will halt the revert process and indicate the files with conflicts. These files will contain special markers.

- Examine the Conflict Markers: Open the conflicted file in a text editor. You’ll see markers like `<<<<<< HEAD`, `=======`, and `>>>>>> [commit-SHA]`. These markers delineate the conflicting sections. The content between `<<<<<< HEAD` and `=======` represents the changes in your current branch (HEAD). The content between `=======` and `>>>>>> [commit-SHA]` represents the changes from the commit being reverted.

- Choose the Correct Version or Merge: Decide which changes to keep. You can:

- Keep the changes from your current branch (HEAD).

- Keep the changes from the commit being reverted (the one specified by the SHA).

- Manually edit the file to create a merged version, incorporating parts of both changes.

- Edit the File: Remove the conflict markers (`<<<<<<`, `=======`, and `>>>>>>`) and modify the code to reflect your chosen changes. This might involve selecting one version, combining parts of both, or rewriting the code entirely.

- Stage the Resolved File: Use `git add

` to stage the resolved file. This tells Git that you’ve resolved the conflict. - Continue the Revert: Use `git revert –continue` to continue the revert process. Git will apply the resolved changes and proceed with reverting other commits if any.

- If more conflicts exist: Repeat the process from step 2 until all conflicts are resolved.

Practical Example of a Merge Conflict Scenario and Resolution

Consider a scenario where two developers, Alice and Bob, are working on a project. Alice commits a change that adds a new feature to a file named `feature.py`. Later, Bob commits a change to the same file, modifying a line that Alice’s commit also changed. If Bob then tries to revert Alice’s commit, a merge conflict will occur. Initial State:* Alice’s Commit: Adds a new function `calculate_sum()` to `feature.py`.

Bob’s Commit

Modifies the `calculate_sum()` function in `feature.py`. Conflict Scenario: Bob attempts to revert Alice’s commit. Git identifies a conflict in `feature.py`. Conflict Markers in `feature.py`:“`pythondef calculate_sum(a, b): <<<<<<< HEAD # Bob's modification: Return the sum with some extra calculation return (a + b) - 2 ======= # Alice's original function return a + b >>>>>>> [Alice’s Commit SHA]“`Resolution using a Merge Tool (e.g., VS Code’s built-in merge tool): Bob opens `feature.py` in VS Code. The editor highlights the conflict.

-

2. VS Code’s merge tool presents three sections

“Current Change” (Bob’s changes, HEAD), “Incoming Change” (Alice’s original function), and “Merged Result”.

- Bob examines both versions of the `calculate_sum()` function.

- Bob decides that Alice’s original implementation is better for the project’s requirements.

- Bob selects the “Incoming Change” (Alice’s original version) in the merge tool.

- The “Merged Result” now contains Alice’s original function.

- Bob saves the file.

- Bob uses `git add feature.py` to stage the resolved file.

- Bob runs `git revert –continue` to complete the revert.

Resolution using Manual Editing:

- Bob opens `feature.py` in a text editor.

- Bob examines the conflict markers and the different versions of the `calculate_sum()` function.

- Bob decides to keep Alice’s original implementation.

- Bob deletes the conflict markers and the code from Bob’s modification, leaving only Alice’s original function.

- Bob saves the file.

- Bob uses `git add feature.py` to stage the resolved file.

- Bob runs `git revert –continue` to complete the revert.

Process for Testing Reverted Changes After Resolving Conflicts

After resolving merge conflicts and completing the `git revert` process, thorough testing is crucial to ensure the code’s integrity and functionality. The following steps Artikel a robust testing process:

- Review the Reverted Changes: Before testing, carefully review the changes that were reverted and the resolved conflicts. This helps to understand the expected behavior after the revert. Use `git diff –stat HEAD^ HEAD` to see a summary of the changes.

- Run Unit Tests: Execute all unit tests associated with the affected code. Unit tests verify the functionality of individual components or functions. If the reverted changes introduced bugs, unit tests should ideally catch them.

- Perform Integration Tests: Run integration tests to ensure that different parts of the system work together correctly after the revert. Integration tests check the interaction between modules, services, or components.

- Conduct Manual Testing: Manually test the functionality that was affected by the reverted commit. This involves interacting with the application or system to verify that the expected behavior is achieved. Manual testing is crucial to identify issues that might not be covered by automated tests.

- Consider Regression Testing: Run regression tests to ensure that existing functionality is not broken by the revert. Regression tests are designed to identify unexpected side effects or regressions caused by code changes.

- Deploy to a Staging Environment: If possible, deploy the reverted changes to a staging environment that mirrors the production environment. This allows for more comprehensive testing in a realistic setting.

- User Acceptance Testing (UAT): If applicable, involve end-users in the testing process to gather feedback and ensure that the reverted changes meet their requirements.

- Address Test Failures: If any tests fail, analyze the failures and address the underlying issues. This may involve fixing bugs, updating tests, or re-evaluating the revert process.

By following this testing process, developers can increase the confidence that the reverted changes are safe and do not introduce any regressions or unexpected behavior.

Reverting Multiple Commits

Reverting a single commit, as discussed previously, is a common task. However, scenarios frequently arise where a series of commits, perhaps introducing a faulty feature or a series of unintended changes, need to be undone. Git provides mechanisms to revert multiple commits, offering flexibility in how these changes are addressed.

Reverting a Range of Commits

Git’s `revert` command, coupled with specific syntax, enables the reversion of a sequence of commits. This is often more efficient than reverting each commit individually, especially when dealing with a substantial number of changes.To revert a range of commits, the primary method involves specifying a range using the commit hashes. The syntax for this is:

`git revert

.. `

It is important to understand how Git interprets this range.

- The command will revert all commits

-between* the two specified commit hashes,

-excluding* the commit specified as ``. - The order of the commits is significant. Git will apply the reverts in the order they were originally committed.

- The commit range uses two dots (`..`) to specify the inclusive range. This is a common way to specify a range in Git.

For instance, if you want to revert commits from `abcdef1` to `fedcba1`, the command would be `git revert abcdef1..fedcba1`. This command will revert all the commits starting from the commit immediately

after* `abcdef1` and up to, and including, `fedcba1`.

Another option is to use the caret (`^`) notation to include a commit.

`git revert

^.. `

This syntax is similar to the two-dot range, but it includes the commit specified as `

and* all commits up to and including `fedcba1`.

Example of Reverting a Series of Commits and Potential Issues

Consider a scenario where a developer introduced a new feature over three commits, resulting in undesirable behavior. These commits have the following hashes: `commit-1: abcdef1`, `commit-2: fedcba1`, and `commit-3: 1234567`. The developer wants to remove the entire feature set.The command `git revert abcdef1..1234567` would revert commits `fedcba1` and `1234567`, effectively removing the changes. The order is important; Git will apply the reverts in the order they were committed.Potential issues that can arise during the reversion of multiple commits:

- Merge Conflicts: Each revert operation, like a merge, can potentially lead to merge conflicts if subsequent commits modify the same lines as the original commits. Resolving these conflicts becomes a crucial step. The developer will need to manually edit the files, resolving the conflicts and staging the changes.

- Dependencies: If the reverted commits have dependencies on each other, reverting them in the wrong order or partially can lead to a broken state. It’s essential to understand the dependencies between the commits before reverting.

- Commit History Clutter: Reverting multiple commits creates a series of new “revert” commits. This can make the commit history more complex and harder to understand, particularly if not well-documented.

For instance, if commit `fedcba1` introduced a change that depended on a change introduced by `abcdef1`, reverting `fedcba1` before `abcdef1` could leave the codebase in an inconsistent state. The developer would need to carefully analyze the code and potentially revert the commits in a different order, or manually edit the code to resolve the dependencies.

Best Practices for Managing and Documenting Reverts of Multiple Commits

Effectively managing and documenting reverts of multiple commits is critical for maintaining a clean and understandable project history. Following these best practices can help mitigate the issues associated with reverting multiple commits.

- Careful Planning: Before reverting multiple commits, carefully analyze the commits to be reverted, understand their dependencies, and plan the reversion strategy. Consider the order in which the commits will be reverted.

- Create a Branch: It’s always a good practice to create a new branch before performing a series of reverts. This allows for easy experimentation and the ability to discard the changes if necessary without affecting the main branch.

- Test Thoroughly: After reverting the commits, thoroughly test the application to ensure that the intended changes have been made and that no new issues have been introduced. This includes unit tests, integration tests, and manual testing.

- Commit Messages: Write clear and descriptive commit messages for each revert commit. The commit message should explain

-why* the commits were reverted, not just

-what* was reverted. Reference the original commit hashes and, if applicable, the issue that prompted the revert. This makes it easier for other developers (and your future self) to understand the history of changes. For example: “Revert: Feature X – introduced bug Y (reverts commit abcdef1, fedcba1, and 1234567)

-resolves issue #123″. - Documentation: Update any relevant documentation to reflect the changes. This might include the project’s README, API documentation, or other relevant documentation.

- Communication: Communicate the changes to the team. Informing other developers about the reverts ensures that everyone is aware of the changes and can adjust their work accordingly. This is especially important in a collaborative environment.

- Use Interactive Rebase (Sometimes): While `git revert` is the recommended approach for reverting public commits, for local commits or more complex scenarios, consider using interactive rebase (`git rebase -i`) to combine, edit, or drop commits before pushing them. However, use this with caution on shared branches.

Advanced Git Revert Techniques

Beyond the fundamental steps of reverting commits, Git provides several advanced options that offer greater control and flexibility in managing your repository’s history. These techniques are crucial for handling complex scenarios and ensuring a smooth workflow, especially in collaborative environments. Understanding these options can significantly improve your ability to recover from mistakes and maintain a clean, understandable project history.

Using the `–no-commit` Option

The `–no-commit` option provides a way to revert a commit without immediately creating a new commit. Instead of automatically creating a new commit with the reverted changes, Git stages the changes in your working directory and index. This allows you to review the changes, make further modifications, or combine the reverted changes with other changes before committing.Here’s how `–no-commit` works:

git revert –no-commit

After running this command, Git will:

- Revert the specified commit.

- Stage the changes in your working directory and index.

- Leave your working directory in a modified state, ready for further adjustments.

This is particularly useful in the following scenarios:

- Combining Reverts: You can revert multiple commits and then commit all the changes together, creating a single commit that reflects the combined effect. This is cleaner than creating multiple revert commits, especially if the reverted commits are closely related.

- Modifying Reverted Changes: You might want to revert a commit but then make minor adjustments to the reverted changes before committing. With `–no-commit`, you can easily edit the files in your working directory before committing the final result.

- Handling Complex Conflicts: While Git’s merge conflict resolution handles many situations, `–no-commit` gives you more control when resolving complex conflicts that arise from reverting a commit. You can manually resolve the conflicts in your working directory before committing.

For example, imagine you reverted a commit that introduced a significant feature, but you now realize you want to keep parts of that feature. Using `–no-commit`, you can revert the commit, manually edit the files in your working directory to retain the desired parts of the feature, and then commit the modified changes. This allows you to selectively undo the changes made by the original commit.

Using the `–abort` Option

The `–abort` option is essential when a revert operation encounters a problem and cannot complete successfully, often due to merge conflicts that cannot be automatically resolved. It provides a way to stop the ongoing revert process and return your repository to its state before the revert command was initiated.The situation when the `–abort` option is most useful:

- During a Revert Conflict: If Git cannot automatically merge the changes during a revert, it will pause the process and ask you to resolve the conflicts. If you’re unsure how to resolve the conflicts or want to abandon the revert, using `–abort` is the way to go.

The command is as follows:

git revert –abort

When you execute this command:

- Git will stop the current revert process.

- It will discard any changes that were made during the revert.

- Your repository will revert to the state it was in before you started the revert operation.

This is a safe and reliable way to back out of a problematic revert operation, ensuring that your repository remains consistent and your project history is not corrupted by partially completed changes. This helps prevent situations where your working directory or index might be in an inconsistent state.

Identifying Scenarios Where Reverting is Not the Appropriate Solution and Suggesting Alternatives

While Git revert is a powerful tool, it’s not always the best solution. Understanding when to avoid reverting and choosing alternative approaches is crucial for maintaining a clean and understandable project history.Consider these scenarios where reverting might not be the best approach:

- Public Branches: Avoid reverting commits on public branches that others are actively working on. Reverting can cause significant confusion and merge conflicts for other developers who have already based their work on the commit being reverted.

- History Rewriting Concerns: Reverting creates new commits that undo the changes. If the commit you’re reverting has already been shared with others, reverting can create conflicting histories. While Git handles these conflicts, it can complicate the workflow.

- Feature Branch Merges: When a feature branch is merged into the main branch, and you subsequently want to remove that feature, reverting the merge commit might not be the best approach. This can create a complex history.

Here are alternative approaches to consider in these situations:

- Creating a New Commit to Fix Issues: Instead of reverting, create a new commit that fixes the issues introduced by the problematic commit. This is often the preferred method on public branches, as it doesn’t rewrite history. This approach preserves the original commit and adds a new commit to address any problems.

- Reverting in a Separate Branch: If you must revert a commit on a public branch, consider doing so in a separate branch. This allows you to address the issue without directly impacting other developers’ work on the main branch. Once the revert is complete, you can merge the branch into the main branch.

- Using `git reset`: If you’re working locally and haven’t pushed your changes, `git reset` can be used to remove commits. Be very careful with `git reset`, as it can permanently remove commits from your local repository. Use this only if you are certain you are working locally and the changes haven’t been shared.

- Cherry-Picking: Instead of reverting an entire commit, cherry-pick specific changes from another commit to fix issues. This gives you more granular control over the changes you’re incorporating.

- Refactoring/Removing Code: If the issue is related to the code itself, refactor or remove the problematic code directly. This keeps the history clean and doesn’t create unnecessary revert commits.

Choosing the right approach depends on the specific situation and your team’s workflow. Consider the impact on other developers, the complexity of the changes, and the overall maintainability of your project history.

Practical Examples

Understanding how to apply `git revert` effectively is best achieved through practical scenarios. These examples demonstrate common use cases and provide step-by-step instructions to safely undo changes, correct mistakes, and maintain a clean project history.

Reverting a Bug Fix

A common scenario involves a bug introduced in a specific commit. Reverting that commit is often the quickest way to restore functionality.To revert a commit that introduced a bug, you’ll need the commit’s SHA-1 hash. You can find this hash using `git log`, which displays the commit history.Here’s how to revert a commit that introduced a bug:

- Identify the Buggy Commit: Use `git log` to find the commit that introduced the bug. Note the commit hash (e.g., `a1b2c3d4`). The output will show information about each commit, including the author, date, and commit message.

- Execute `git revert`: Run the command `git revert a1b2c3d4` (replace `a1b2c3d4` with the actual commit hash). This command creates a new commit that undoes the changes introduced by the specified commit.

- Review the Changes: Git will likely open a text editor with the commit message for the revert commit. Review the message and edit it if necessary. The default message usually starts with “Revert ” followed by the original commit message.

- Save and Close: Save the commit message and close the editor. Git will then create the revert commit.

- Test: Thoroughly test your code to ensure the bug is resolved and no new issues have been introduced.

- Push the Revert Commit: If everything is working correctly, push the revert commit to the remote repository using `git push`.

For instance, imagine a commit with the message “Fix: Incorrect calculation in order total” introduced a bug. After reverting this commit, the order totals would revert to their previous, correct calculations.

Reverting an Unnecessary Feature

Sometimes, a feature is implemented but later deemed unnecessary or detrimental to the project’s goals. Reverting the commit that introduced the feature removes it from the codebase.To revert a feature, the process is similar to reverting a bug fix.Here’s the process to revert a commit that added an unwanted feature:

- Locate the Feature Commit: Use `git log` to identify the commit that added the feature. Note its SHA-1 hash.

- Revert the Commit: Execute `git revert [commit_hash]`, substituting the actual commit hash.

- Review the Commit Message: Git will open a text editor for the revert commit message. Modify it if needed to clarify the reason for the removal.

- Save and Close: Save the commit message and close the editor.

- Test the Project: Ensure the feature is removed and the project functions as expected.

- Push the Changes: Use `git push` to push the revert commit to the remote repository.

For example, if a commit “Add: Experimental social media integration” was later decided against due to performance issues, reverting that commit would remove the social media integration.

Reverting a Commit Containing Sensitive Information

Accidentally committing sensitive information (passwords, API keys, etc.) is a serious security risk. Reverting the commit and taking further steps is crucial to mitigating this risk.Reverting a commit containing sensitive data requires a multi-step approach to ensure the information is removed from the repository and its history.Here’s a guide to reverting a commit with sensitive data:

- Identify the Sensitive Commit: Use `git log` to locate the commit containing the sensitive information. Note the commit hash.

- Revert the Commit: Execute `git revert [commit_hash]` to remove the changes.

- Review the Commit Message: Review and adjust the commit message of the revert commit as needed.

- Remove the Sensitive Data: Immediately remove the sensitive data from your working directory and all relevant files.

- Commit the Removal: Create a new commit to remove the sensitive information from the files. This is important to ensure the information is not present in the latest version of the code. Use a clear commit message, such as “Remove sensitive data”.

- Rewrite History (If Necessary): This step is optional, but highly recommended to remove the sensitive information from the repository’s history. This can be done using tools like `git filter-branch` or `git filter-repo`. These tools rewrite the commit history to remove the offending commit entirely or replace the sensitive information with placeholders. Be extremely cautious when using these tools, as they can significantly alter your repository history and require careful handling.

- Force Push (If History is Rewritten): If you’ve rewritten history, you’ll need to force push the changes to the remote repository: `git push –force`. Warning: Force pushing can overwrite other people’s work. Communicate with your team before force pushing.

- Revoke and Rotate: If the sensitive information was used, revoke the compromised credentials and rotate them. Generate new API keys, change passwords, etc.

- Notify: Inform relevant stakeholders (e.g., security team, project leads) about the incident and the steps taken to remediate it.

For example, imagine a commit “Add: API key for production access” accidentally included the API key directly in a configuration file. Reverting this commit, removing the API key from the config file, and rotating the key would be essential to protect the system.

Git Revert Visual Aids and Comparisons

This section provides visual aids and comparative analyses to further solidify your understanding of `git revert`. We will explore a visual representation of the `git revert` process, a step-by-step guide, and a comparison table highlighting the differences between `git revert` and other Git commands. This will help you visualize the process and understand its nuances more effectively.

Visual Representation of the Git Revert Process

The following is a detailed description of the `git revert` process, which can be imagined as a timeline.Imagine a timeline representing your Git repository’s commit history.

1. Initial State

The timeline begins with several commits, each represented by a node. These commits are labeled chronologically (Commit A, Commit B, Commit C, etc.) and represent changes made to the codebase.

2. Target Commit

We select a specific commit to revert (e.g., Commit C). This commit contains the changes we want to undo.

3. Revert Operation

`git revert` is executed on Commit C. The command analyzes the changes introduced by Commit C.

4. Revert Commit Creation

Git creates a new commit, known as the “revert commit.” This new commit’s content is the inverse of the changes made in Commit C. If Commit C added a line of code, the revert commit removes it. If Commit C deleted a file, the revert commit re-adds it. The revert commit is placed on the timeline, typically after the original commit.

It’s important to note that the original commit (Commit C) remains in the history.

5. Timeline Progression

The timeline now shows the original commits (A, B, C, etc.) and the new revert commit. The revert commit effectively “undoes” the changes introduced by Commit C, bringing the codebase to a state as if Commit C never happened, but without removing Commit C itself from the history.

6. Impact

The codebase now reflects the state before Commit C, while the history retains the complete sequence of changes, including the revert action. This ensures a clean history, allowing for auditing and collaboration.

Step-by-Step Guide to Executing Git Revert

To understand the `git revert` process better, here is a numbered list that Artikels the key steps involved:The following list breaks down the process of using `git revert` effectively. Each step is crucial for a successful revert operation.

- Identify the Commit to Revert: Determine the specific commit you wish to undo. You can use `git log` to view the commit history and identify the commit’s hash (the unique identifier).

- Execute the `git revert` Command: Use the command `git revert

`, replacing ` ` with the hash of the commit you want to revert. - Handle Potential Conflicts: If the revert introduces conflicts (due to subsequent changes that overlap with the original commit), Git will alert you. You’ll need to resolve these conflicts manually by editing the affected files.

Remember to resolve conflicts carefully, ensuring that the resulting code reflects the desired state.

- Commit the Revert Changes: After resolving any conflicts, Git will prompt you to commit the revert changes. You can accept the default commit message or edit it to provide more context.

- Verify the Revert: Review the commit history (using `git log`) to confirm that the revert commit has been created and that the changes have been successfully undone.

Comparison of Git Revert with Other Git Commands

The following table compares `git revert` with other commonly used Git commands to illustrate their differences and appropriate use cases. Understanding these distinctions is critical for choosing the correct command for your needs.

| Command | Purpose | Effect on History | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

git revert |

Undoes the changes introduced by a specific commit. | Creates a new commit that reverses the changes of the target commit, preserving the original commit in the history. | Safely undoing a specific commit in a public branch, maintaining a complete and accurate history. |

git reset |

Moves the branch pointer to a different commit. | Can discard commits, move the branch pointer, or unstage changes, modifying the commit history. | Removing a series of commits from a local branch or undoing changes before they are committed (with `–soft`, `–mixed`, or `–hard` options). Be careful with the hard option, as it can lead to data loss. |

git checkout |

Switches branches or restores working tree files. | Can move the HEAD pointer to another branch, discard local changes in the working directory, or restore specific files to a previous state. | Switching between branches, discarding local changes in the working directory, or restoring individual files. |

git cherry-pick |

Applies a specific commit from one branch to another. | Creates a new commit on the current branch that has the same changes as the specified commit. | Applying specific commits from another branch to the current branch. Useful for backporting fixes. |

Best Practices and Considerations

Reverting commits is a powerful tool, but it’s crucial to use it responsibly to maintain a clean and understandable project history. This section provides guidelines for documenting reverts, communicating them effectively within a team, and mitigating potential issues, especially in public repositories. Following these best practices ensures that your team can understand the project’s evolution and collaborate effectively.

Documenting Reverts in Commit Messages

Clear and concise commit messages are essential for understanding the reasons behind changes, especially when reverting commits. Proper documentation simplifies future troubleshooting and helps team members grasp the project’s development history.To effectively document reverts, follow these guidelines:

- Clearly State the Purpose: Begin your commit message with a clear and concise statement of the reason for the revert. For example, “Revert: Fix: Incorrect calculation in the sales report” or “Revert: Introduce feature X due to performance issues.” This immediately informs readers about the commit’s intent.

- Reference the Original Commit: Include the commit hash of the commit being reverted. This creates a direct link between the revert and the original commit. For instance, “Revert: Fix: Incorrect calculation in the sales report (reverts commit a1b2c3d4).”

- Explain the Reasoning: Briefly explain why the original commit was reverted. Provide context regarding the bug, performance issue, or other problem that necessitated the revert. This helps others understand the rationale behind the change.

- Provide Context: Include any relevant information, such as the impact of the original commit, the steps taken to identify the problem, and any alternative solutions considered.

- Maintain Consistency: Adopt a consistent format for your revert commit messages across the project. This improves readability and makes it easier to search for and understand reverts.

Communicating Reverts to Team Members

Effective communication is vital in a collaborative environment. When reverting a commit, inform your team members promptly and transparently to prevent confusion and ensure everyone is on the same page.Here’s how to effectively communicate reverts:

- Notify the Team: Immediately notify the team about the revert, ideally through channels like Slack, Microsoft Teams, or email. This ensures everyone is aware of the change.

- Provide Context: Explain the reason for the revert and its potential impact on other developers. Clearly state what has been reverted and why.

- Discuss Alternatives: If possible, discuss the alternative solutions considered and why the revert was chosen. This demonstrates a thoughtful approach to problem-solving.

- Encourage Questions: Invite team members to ask questions and clarify any confusion. This fosters a collaborative environment where everyone can understand the project’s state.

- Update Documentation: If the revert affects any documentation, update it promptly. This includes any project documentation, user manuals, or API references.

Mitigating Problems in Public Repositories

Reverting commits in public repositories requires extra care. Since changes are visible to a broader audience, it’s important to minimize the potential for confusion or disruption.To mitigate problems, consider these points:

- Prioritize Thorough Testing: Before reverting, thoroughly test the changes that led to the original commit. Ensure that the revert does not introduce new problems or regressions.

- Consider Alternatives: Before reverting, explore alternative solutions, such as bug fixes or temporary workarounds. Only revert if the original commit poses a significant problem that cannot be easily addressed otherwise.

- Provide Detailed Explanations: In your revert commit message, provide a detailed explanation of why the commit was reverted, including the problem’s impact and any alternative solutions considered. This helps users understand the change and its rationale.

- Inform Users: If the revert affects any public-facing features or APIs, inform your users about the change. Provide clear instructions on how to handle the revert, such as updating their code or configuration.

- Use Branches for Reverts: If possible, perform reverts on a dedicated branch. This allows you to isolate the revert and thoroughly test it before merging it into the main branch.

- Monitor for Feedback: After reverting, monitor for user feedback and address any issues that arise promptly. This demonstrates your commitment to providing a stable and reliable product.

Outcome Summary

In conclusion, mastering `git revert` is an essential skill for any developer. By understanding its mechanics, practicing safe procedures, and knowing how to handle conflicts, you can effectively manage your project’s history. This guide has provided a roadmap to undo commits safely, empowering you to correct mistakes, remove unwanted features, and ultimately, maintain a robust and reliable codebase. Remember to always document your reverts and communicate effectively with your team to ensure a smooth collaborative workflow.